A New Jersey resident generates and stores all the power he needs with solar panels and hydrogen

EAST AMWELL, N.J.—Mike Strizki has not paid an electric, oil or gas bill—nor has he spent a nickel to fill up his Mercury Sable—in nearly two years. Instead, the 51-year-old civil engineer makes all the fuel he needs using a system he built in the capacious garage of his home, which employs photovoltaic (PV) panels to turn sunlight into electricity that is harnessed in turn to extract hydrogen from tap water.

“The ability to make your own fuel is priceless,” says the man known as “Mr. Gadget” to his friends. He boasts a collection of hydrogen-powered and electric vehicles, including a hydrogen-run lawn mower and car (the Sable, which he redesigned and named the “Genesis”) as well as an electric racing boat, and even an electric motorcycle. “All the technology is off-the-shelf. All I’m doing is putting them together.”

“I’m a self-sufficiency guy,” he adds. Strizki, a civil engineer, has been interested in alternative energy sources since 1997 when he began working on vehicles fueled by alternative means during his tenure with the New Jersey Department of Transportation.

Strizki’s two-story colonial on an 11-acre (4.5 hectare) plot 12 miles (19 kilometers) north of Trenton is the nation’s first private hydrogen-powered house, which he now shares with his wife, two dogs and a cat. (His two daughters and son, all in their 20s, have left the nest.) It has been running entirely on electricity generated from the sun and stored hydrogen since October 2006, when Strizki—in a project that his wife Ann fully supports—built an off-grid energy system with $100,000 of his own cash and $400,000 in grants from the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities, along with technology from companies such as Sharp, Swagelok and Proton Energy Systems.

The Strizki’s personalized home-energy system consists of 56 solar panels on his garage roof, and housed inside is a small electrolyzer (a device, about the size of a washing machine, that uses electricity to break down water into its component hydrogen and oxygen). There are 100 batteries for nighttime power needs along the garage’s inside wall; just outside are ten propane tanks (leftovers from the 1970s that are capable of storing 19,000 cubic feet, or 538 cubic meters, of hydrogen) as well as a Plug Power fuel cell stack (an electrochemical device that mixes hydrogen and oxygen to produce electricity and water) and a hydrogen refueling kit for the car.

On a typical summer day, the solar panels drink in and convert sunlight to about 90 kilowatt-hours of electricity, according to Strizki. He consumes about 10 kilowatt-hours daily to run the family’s appliances, including a 50-inch plasma television, along with his three computers and stereo equipment, among other modern conveniences.

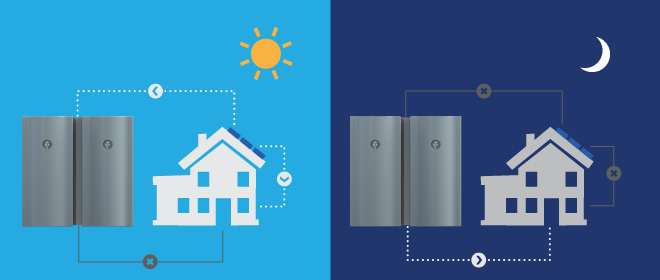

The remaining 80 kilowatt-hours recharge the batteries—which provide electricity for the house at night—and power the electrolyzer, which splits the molecules of purified tap water into hydrogen and oxygen. The oxygen is vented and the hydrogen goes into the tanks where it is stored for use in the cold, dark winter months. From November to March or so Strizki runs the stored hydrogen through the fuel cell stacks outside his garage or in his car to power his entire house—and the only waste product is water, which can be pumped right back into the system.

“I can make fuel out of sunlight and water—and I don’t even use the water,” he notes. “If it’s raining, it’s fuel. If it’s sunny, it’s fuel. It’s all fuel.”

The modular home—built in 1991—looks like a typical suburban house; its top-of-the-line insulation and energy-efficient windows look no different, and the facade hides the hydrogen-powered clothes dryer and geothermal system for heating and cooling, which pumps Freon gas underground to harvest heat in winter and cool in summer.

“Geothermal is another piece of free energy,” Strizki says, noting that he dug eight feet (2.4 meters) down into the granite under his home to take advantage of the constant 56-degree Fahrenheit (13-degree Celsius) temperature underground. In summer he can use the lower temperatures underground to cool his entire house, and in winter he can capture those warmer temperatures, supplementing them with a heat pump powered by electricity from hydrogen. “Nothing goes to waste.”

This year, Strizki is hardly running his $78,000 Hogen electrolyzer (manufactured by Proton Energy Systems in Connecticut, a company that makes hydrogen-generation equipment) because last year’s mild winter left him with full tanks. When he does turn it on, the excess hydrogen vents from a small pipe on the roof with the sound of an impolite burp.

That vented hydrogen speeds at 45 miles (72 kilometers) per hour through the atmosphere on its way off the planet—one of only two gases, the other being helium, that escapes into space entirely because it is lighter than air. In fact, Strizki’s quarter-inch thick propane tanks weigh less when filled with hydrogen than when depleted.

Of course, hydrogen is a highly flammable gas, but its quick escape eases Strizki’s fears that it might ignite or explode. It “disperses faster than any other gas,” he notes. “Hydrogen won’t sit around waiting for a flame.”

The final piece of Strizki’s energy solution is dubbed “Genesis,” his $3-million aluminum Mercury Sable, one of 10 that carmaker Ford produced in the 1990s to test how well the lighter metal would fare in crash tests. Ford gave Strizki the special model to drive in the Tour de Sol solar car race in New Jersey in 2000. Strizki installed a 104-horsepower electric engine (compared with a Toyota Prius’s 44-horsepower motor) that can reach speeds of 140 miles (225 kilometers) per hour. Pop the hood and next to the electric engine sit two fuel cell stacks that convert hydrogen and oxygen into water and electricity, propelling the electric engine forward smoothly and quickly.

The car never competed because it was not ready in time, but the unique vehicle does hold the world record for farthest travel on a single charge: 401.5 miles (646.2 kilometers), a distance which Strizki drove in December 2001. Today, Genesis shares the road with a variety of less costly fuel cell cars: Honda’s new hydrogen-powered FCX Clarity, which hit the market this week leasing for $600 a month, as well as the hydrogen-powered Chevrolet Equinox test-vehicle fleet from General Motors—part of a pilot program that aims to determine how hydrogen cars might function in everyday life. Both the Japanese and U.S. automakers are betting that these nonpolluting cars will one day replace the internal combustion engine.

GM is committed to building a “mass volume” of its hydrogen fuel cell powered Equinoxes in coming years, according to Larry Burns, GM’s vice president of research and development, but only if a way to refuel them exists. As it stands, the entire nation has just 122 hydrogen stations—compared with 170,000 gasoline and diesel stations.

This is part of the reason that not everyone is a fan of hydrogen. Former U.S. Department of Energy official Joseph Romm, a physicist, notes that it’s a waste of time and electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen instead of just using the electricity directly in an all-electric, plug-in hybrid car. The debate boils down to whether batteries or hydrogen are a better way to store and deliver electrical energy.

But Strizki argues that hydrogen offers benefits that batteries do not. For example, GE Global Research found that hydrogen might prove a better way to store electricity generated by renewable resources in remote areas—such as wind farms in North Dakota or solar arrays in New Mexico—than building expensive and costly electric transmission lines. Instead, the hydrogen generated in such locations could be pumped nationwide through existing natural gas pipelines, providing fuel for a fleet of hydrogen-powered vehicles.

Regardless of whether those future vehicles are powered by hydrogen or rechargeable batteries, both would move using an electric motor that does not require polluting (and newly expensive) fossil fuels. And they would come with another important extra benefit: the batteries or hydrogen fuel cells that run the car could also serve as a backup energy source for the home. “I can plug this car into my home and run it,” Strizki notes.

Strizki is now working to bring the price down enough to make homes powered by the sun and hydrogen affordable for average consumers. He says that he can build a solar-hydrogen system for as little as $90,000, thanks to dipping costs for solar panels and lessons learned in building his home. Even at that price, however, the off-grid system would be expensive compared with annual electric bills in New Jersey that average $1,500, although that number has been increasing every year, including a jump of as much as 17 percent this year.

But add gasoline costs to that—which average more than $3,000 annually, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration—and the price becomes more reasonable, particularly because the EIA figures were calculated back when gasoline was $2 per gallon rather than the present $4. “It didn’t make sense when gas was $1 but now at $4? A lot of things that didn’t make sense, now make a lot of sense,” Strizki says.

He is already overseeing construction of the second such home-energy system—estimated to cost $150,000—for a wealthy client in the Caribbean.

The backyard tinkerer is also working with several potential clients to construct off-grid homes in New Jersey, New York State and even Colorado, and has quit his most recent job as an installer of solar energy systems to concentrate full-time on the company he co-founded to promote the homes: Renewable Energy International. The key to bringing the price down will be newer, better generations of the component technology, particularly the electrolyzer. Fuel cell manufacturers such as ReliOn in Spokane, Wash., are already taking a page from the computer industry—employing removable individual fuel cells, known as “blades,” similar to the computer blades in data centers, that can be changed individually if problems occur.

Ultimately, this suburban home may become the first of a coming hydrogen-electric economy—one that eliminates or sharply reduces the greenhouse gas emissions causing climate change—or merely another technological dead end, like Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome or dymaxion car.

“The only way to get a zero-carbon footprint is to grab the big power plant in the sky,” Strizki says. “Maybe [the solar-hydrogen house] is too expensive, maybe not as efficient as they like, but no one is saying it doesn’t work.”

Credit: David Biello , Scientific America